THE IRISH TIMES

June 22, 2018

Freedom and liberal democracy must return to States

Trinity’s honouring of Hillary Clinton taps into desire to turn tide on Trump

July 4, 2017

Time to tackle the emerging crisis in Irish American identity

The effective absence of a new generation of Irish immigrants has raised important new questions

January 18, 2017

Professor Ronan Fanning: A giant of Irish historiography

Ted Smyth reflects on the incisive intellect and modern mind that was Prof Fanning

December 31, 2016,

Sir Robert Armstrong: ‘Nothing will ever be the same again in NI’

State papers 1986: UK secretary said Anglo-Irish Agreement resulted in ‘fundamental change’

December 28, 2016

Democrats face eight hard steps to retake the White House

Despite catastrophic loss to Donald Trump, the pulverised party can still pick itself up

November 14, 2015

New Ireland Forum helped begin process of changing hearts and minds

Shift in nationalist demands allowed forum to become launchpad for lobbying

Freedom and liberal democracy must return to States

Trinity’s honouring of Hillary Clinton taps into desire to turn tide on Trump

By Ted Smyth

June 22, 2018

Hillary Clinton: won the popular vote in the American presidential election

by three million votes but failed to carry the electoral college. Photograph: Timothy A Clary/AFP/GettyLiberal democracy and freedom are under assault in America to an extent not seen since the 1930s. Prof Timothy Snyder reminds us in his book, On Tyranny, that both fascism and communism “were responses to globalisation, to the real and perceived inequality it created, and the apparent helplessness of the democracies in addressing them”. Snyder believes “it could happen here” and that independent judges and journalists are our main defence against tyranny in America as President Donald Trump tramples on human rights and freedom supported by a Republican-controlled Congress.

Many of us in America spent the past year saddened and outraged by the American president’s collusion and cruelty, compounded by his lies and attacks on our media, judges and allies. Now there is a growing determination to fight for liberal democracy and to defend its institutions and values. We are moving beyond protest to organising at local level, registering voters and selecting talented candidates for coming elections at municipal, state and federal levels.

Many of us in America spent the past year saddened

and outraged by the American president’s collusion and cruelty,

compounded by his lies and attacks on our media, judges and alliesThis is also a good time to honour the champions of liberal democracy which is why I applaud Trinity College for awarding an honorary degree to Hillary Clinton, a consistent champion of human rights around the world and of equal rights in Northern Ireland. Nearly two long years ago, Clinton won the popular vote in the American presidential election by three million votes but failed to carry the electoral college. Her loss was in part due to Russian manipulation of voters through social media and, as the recent inspector general’s report from the US department of justice confirms, to former FBI director James Comey twice breaking with protocols to disclose internal investigations of her emails. It is clear that Comey owes Clinton an apology for double standards in publicising her investigation but not that of Trump for potential Russian collusion.

New Deal

Hillary’s policies in the 2016 presidential campaign enshrined the same values of liberal democracy as those espoused by Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal which helped keep America free from fascism. Speaking at the Democratic national convention in July 2016, she said, “If you believe that companies should share profits with their workers, not pad executive bonuses, join us. If you believe the minimum wage should be a living wage . . . and no one working full time should have to raise their children in poverty . . . join us. If you believe that every man, woman, and child in America has the right to affordable healthcare . . . join us.”She promised “to make college tuition-free for the middle class and debt-free for all” a crucial contribution to social fairness when 44 million American Millennials and Gen Z’s are suffering under $1.5 trillion (yes trillion) in student debt.

I saw Hillary in Pittsburgh two days after that convention when she attracted large audiences with her message that something radical needed to be done for ordinary Americans. This was the same Hillary who had hung out with the Latina housekeepers in Las Vegas hotels at 1am during the primary against Bernie Sanders, the same Hillary who stood up for racial and sexual equality all her life.

And Hillary’s warnings about Trump were prescient: “He wants to divide us – from the rest of the world, and from each other. He’s taken the Republican Party a long way . . . from Morning in America to Midnight in America.”

America’s political and social woes stem largely from the productivity-pay gap. For 25 years from the late 1940s to the 1970s, the wages and benefits of workers rose in tandem with productivity. According to the Economic Policy Institute, this changed drastically in the 1970s; from 1973 to 2016 productivity rose by 73.7 per cent while hourly pay essentially stagnated, rising by 12 per cent. For example, when I was at the Heinz company in the late 1980s, low-skilled hourly workers earned $40 an hour in pay and benefits. Today such workers are lucky to earn $20 an hour, with direct-benefit pensions ended. The result is that the median savings account balance is $5,200, not enough to pay for a health emergency and totally inadequate in a society where the safety net has been ripped apart.

Rogue capitalism

The system has become rigged in favour of capital at a time when workers have largely lost strike power due to labour competition from Asia and robotics.This is not democratic capitalism, it is rogue capitalism where, as Warren Buffett famously complained, his secretary pays a higher percentage of her income in taxes than he does. Jack Bogle, founder of the $5 trillion index fund Vanguard likens Wall Street to a casino where the croupiers during the past decade “have raked in something like $565 billion each year from you and your fellow investors.” That’s half a trillion dollars that should instead have gone to the pension funds of teachers, nurses and other hard-working Americans.

Bogle believes that free market capitalism has failed, that “Adam Smith’s invisible hand in which pursuing our own self-interests leads to the good of society no longer works in an age of giant global corporations”.

Bogle believes free market capitalism has failed, that 'Adam Smith’s

invisible hand...no longer works in an age of giant global corporations'Who will fight for liberal democracy in America in 2018 and beyond? The good news is that this year thousands of young people have become active in Democratic party politics and labour unions at local and national level. One of them is Conor Lamb who was elected to the House of Representatives last March in a special election in a Pittsburgh district that Trump had won by 19 points. Lamb, a former marine whose uncle is honorary consul for Ireland, won by focusing the voters on his opponent’s record of undermining pensions and unions, not becoming distracted by wedge issues like race, abortion and gun laws.

The immediate goal of those who would protect liberal democracy in America is to win the House for Democrats in November, a tough task given Trump’s gift for promoting racist fears and divisions and the millions of dollars in dark money pumped into negative advertising and social media. A Democratic House would hold hearings on White House corruption and provide a platform for advocating progressive reforms.

As for the presidential election in 2020, in light of the fact that, nearly two years after the election, Trump’s tax legislation and failure to introduce an infrastructure plan or address low wages has made millions of Americans even poorer and angrier, a successful Democratic candidate for president in 2020 better look like he/she is going to restore the American dream of fair wages, security in retirement and affordable education and healthcare. And defend the institutions of freedom and liberal democracy.

Ted Smyth is a former Irish diplomat, business executive and a public affairs consultant based in New York City

John Deasy, appointed by the Taoiseach to work as special envoy to the US on immigration reform

The demise of Irish American identity has often been predicted due to intermarriage with other ethnic groups and the churches ceasing to be an Irish American convening point. Nevertheless Irish and Scots Irish identity has endured amongst forty-one million Americans largely thanks to the waves of new generations of Irish immigrants who refresh and fortify the links with Ireland. Today, however, the effective absence of a new generation of immigrants from Ireland for the first time in 200 years is causing increasing concern that the crisis in Irish American identity is real.

Irish America is by any standards a strategic and crucial asset for Ireland in economic, political and cultural terms. Irish Americans love Ireland in the way Irish people love Ireland. For them, Ireland is an emotional place in the mind, invoking the aesthetics of memory and longing. Yes, Ireland is a real place, but it’s also a place in the imagination. Irish American identity is informed both by being Irish and by not being in Ireland. The greatest novel of the twentieth century was written by an Irishman, who did not live in Ireland, but who was obsessed by Ireland, and wrote about it in exquisite detail.

The question is, what can we do to sustain Irish American identity in the twenty-first century? Two answers immediately suggest themselves. First, lobby for immigration reform and second, increase the investment in Irish cultural programs in America.

The appointment of John Deasy to work on immigration reform demonstrates that the new Taoiseach has a personal appreciation of the challenges faced by diasporas, and a willingness to try new initiatives. It is unlikely that comprehensive immigration reform will be soon achieved in a divided Washington, but there is room for tactical progress to benefit Irish people in America, as Australia and other countries have shown.

Second, a joint campaign led by the Irish government and Irish American leaders would significantly enhance the growth of Irish culture and studies in American colleges and schools, and in Irish American centres. The Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the Minister for the Diaspora lead the Irish Abroad Unit, which would be central to developing a new strategy to foster Irish studies amongst the next generation of Irish Americans.

Barbara Jones, who has been a much-admired Irish Consul General in New York for four years, believes that “Irish culture is today the heart and soul of Irish America, uniting us all in a shared understanding.”

The Irish American writer, Peter Quinn, agrees: “ Ireland feeds off the energy of American diversity and America off the originality and vitality of Irish culture. Irish-American identity can’t survive without its connection to Irish culture, and Irish culture will suffer without its connection to Irish America and the avenue it opens to the wider American culture”.

In order to nourish the heart and soul of Irish America, we should learn from Jewish American organizations, which have invested heavily in Jewish educational programs for young people in schools and universities. According to a Pew Research survey in 2013, American Jews see being Jewish as more a matter of ancestry, culture and values than of religious observance. By the 1990s nearly 40 percent of Jewish children enrolled in a Jewish educational program.

Importantly, there is a demand for Irish culture amongst Irish Americans who are third, fourth and fifth generation. A recent survey by NYU’s Glucksman Ireland House and UCD on IrishCentral.com shows that 85 percent are interested in Irish studies, if courses were available locally. Importantly, 75 percent are interested in distance learning courses in Irish history and literature.

However, professors in Irish studies programs in American universities face stiff competition for funding at a time when student enrolment in American colleges has peaked, state funding is declining, and STEM and other ethnic courses battle for resources. Successful Irish Studies centres in NYU, Notre Dame and Boston College have been supported by the generosity of families like the Glucksmans, Keoughs, Burns and Naughtons. But where is the next generation of Irish American philanthropists who will endow Irish studies and arts programs in America? Many believe that the Irish government could inspire that next generation to come forward with a high profile campaign.

A key player in this new strategy would be the American Conference for Irish Studies (ACIS), which since 1962 has coordinated and enhanced the approximately 1500 Irish studies courses offered every year in 500 American colleges. At this year’s National Meeting of ACIS, more than 200 papers were presented on a range of Irish studies, including Irish Immigration, Seamus Heaney, John Banville, James Joyce, Joseph O’Connor, Frank McCourt, Claire Keegan, Modern Drama and Evolving Identities in Irish America, Post-Secularism in Ireland, Irish Traditional Music in America, Justice and Conflict after the Troubles, and Women’s Bodies in 21st Century Ireland.

The President of ACIS, Professor Timothy McMahon of Marquette University, agrees that reaching young people is essential; he is focused on “fostering the work of younger scholars, both postgraduate students and early career faculty, so that we can build the next generation of teachers and researchers as our own mentors did”. He also wants to “enhance ties to the Irish and Irish-American communities among which we work every day”.Regional ACIS conferences will follow this year at locations across the US.Next June, the National conference takes place at University College, Cork.

On the Irish culture front, there are promising signs in New York City of a renaissance, but it needs to be replicated in other cities. The Irish Repertory Theatre and the Irish Arts Centre are growing in NYC, Professor Joe Lee is Chair of Glucksman Ireland House at NYU where students earn a Masters in Irish Studies, Colm Tóibín is leading Irish literature studies at Columbia University, and Paul Muldoon’s “Irish Picnic” regularly convenes the best in Irish and Irish American performers.

The Irish American writer and New York Times columnist, Dan Barry, succinctly summarizes why culture matters: “A place like Glucksman Ireland House - whose mission, I think, should be expanded even more - is the perfect example of the twinning of art and scholarship to remind us who we are and where the hell we might be going”.

This is not a bad rallying cry as we strive to sustain what it is to be Irish and Irish American in the 21st century.

Ted Smyth is a former Irish diplomat, business executive and a public affairs consultant based in New York City.

Professor Ronan Fanning: A giant of Irish historiography

Ted Smyth reflects on the incisive intellect and modern mind that was Prof Fanning

By Ted Smyth

January 18, 2017

The death of Ronan Fanning, a member of the Royal Irish Academy, professor emeritus of Modern History at University College Dublin and former president of Irish Historical Sciences, is a serious blow to Irish historiography, to Irish political analysis and a tragic loss to his many friends. The son of an Irish doctor and English Montessori teacher, Prof Fanning received his undergraduate degree from UCD and his doctoral thesis on “Balfour and Unionism” from Cambridge University. He was not only a brilliant scholar, but also a stylish writer who brought to his research a critical and independent judgment and an understanding of the intrigue and power struggles that characterize politics.

Possessed of a quick wit and a low tolerance for mediocrity, he took a special pleasure in understanding the personalities of politicians, generals and civil servants as they managed profound and unexpected challenges. Those who were lucky to be his friends or colleagues will remember his lively curiosity, his relish for good political gossip, his vivacious energy and love for being in the thick of things.

These qualities enabled Prof Fanning to provide invaluable context when he wrote on current or historical affairs. Last June, for example, he wrote in the Irish Times, “Brexit is Ireland’s biggest policy test since the second World War . . . the only global crisis since the establishment of the Republic in 1937-38 that has seriously threatened our pursuit of an independent foreign policy.”

Seminal work

In 1978, he wrote the outstanding book, The Irish Department of Finance, (1922-1958), hailed as a pioneering work on the transfer of power from the British government to the Irish administration of William Cosgrave and later to that of Éamon de Valera. The book describes the perennial struggle by politicians and civil servants to balance the budgets while also trying to fulfil the developmental promises of the Irish revolution. Sadly, it would not be until the 1960s that Ireland would escape the economic disadvantages of being a small, agricultural economy subject to the cheap food policy of Britain and beset by the Great Depression, the second World War and the recession of the 1950s.

Perhaps Prof Fanning’s most arresting book was Fatal Path, British Government and Irish Revolution, 1910-1922, published in 2013. The book illustrates how Ireland was a pawn in the efforts by Asquith and Lloyd George to preserve their prime ministerial careers.

As Prof Joe Lee wrote in the Irish Times’ review of the book, “Both (Prime Ministers) had to spend more time calculating the consequences of their policies for internal British politics, and their own positions, than for Anglo-Irish relations.” Prof Lee continues: “All this Fanning delineates with superb command of his material, not least in decoding the significance of what is not said as well as what is said in the innumerable documents he fillets, making it a joy to savour the brushwork of a master of his craft at the top of his form.”

Prof Fanning had a keen understanding of the importance of Irish American nationalism on Irish politics in the 20th century. This is well illustrated in chapter seven of Fatal Path, “Blood in their Eyes: The American Dimension”, a reference by the British ambassador to the US regarding Irish American attitudes to Britain.

Fulbright Professor

On a personal level I had the privilege of getting to know Professor Fanning and his late wife Virginia (and young toddler, Timothy) when he was Fulbright Professor at Georgetown University in Washington DC in 1976-1977, researching the triangular relationship between Britain, Ireland and the US.

Prof Fanning’s timing was particularly good as he received a unique insight into the diplomatic manoeuvring that led to the August 1977 groundbreaking statement by then US president Carter (strongly resisted by the British government and state department), which recognised an official role for Ireland in a solution to the Northern Ireland conflict. Prof Fanning later documented the enormously positive role that then US presidents Reagan and Clinton made to the peace process as it developed following the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985.

In a review in the Guardian, Diarmaid Ferriter described Professor Fanning’s most recent book, Éamon de Valera: A Will to Power, as “stylishly written, accessible, full of clarity and mature assessments”.

Roy Foster in a review in the London Spectator described it as a “crisp, economical but deeply thought-provoking biography”. In an earlier entry on “Dev” in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, Fanning gives De Valera credit for protecting the security of the State.

However, he does not shrink from describing how De Valera inflamed the Civil War: “De Valera, in other words, was largely responsible for the dimensions, if not for the fact, of the civil war. By allowing those who took up arms against the treaty to draw on his authority, he conferred respectability on their cause it could never have otherwise attained. His behaviour in the immediate aftermath of the Treaty, in sum, was petulant, inflammatory, ill judged, and profoundly undemocratic.”

Journalism

Anyone who wants to read a short but brilliant account of Ireland since 1922 should obtain Prof Fanning’s Independent Ireland published in 1983 in the Hellicon series of Irish History. The book cover depicts a cartoon in Dublin Opinion from July 1948 showing the removal of the statue of Queen Victoria from the front of the Irish parliament building. She is looking down at an enigmatic De Valera saying, “Begob, Eamon, there’s great changes around here.”

For many years Prof Fanning wrote on current affairs in the Sunday Independent and in 2009 co-wrote with former diplomat, Michael Lillis, a biography of Eliza Lynch. The book uses primary sources to rescue the Cork-born “Queen of Paraguay” from her notorious reputation invented by Paraguay’s enemies in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay.

As the relationship between Ireland and Britain changes post Brexit, and as US president-elect Donald Trump takes office in the United States, it remains to be seen what international role Ireland can play as the sole English-speaking member of the EU.

It is our loss that Ronan Fanning will not be writing authoritatively and incisively on these challenging times.

Ted Smyth is a former Irish diplomat and chairman of the Advisory Board of UCD Clinton Institute

‘Nothing will ever be the same again in NI’

State papers 1986: UK secretary said Anglo-Irish Agreement resulted in ‘fundamental change’

by John Bowman

December 31, 2016,

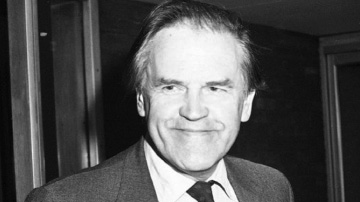

British Cabinet secretary Sir Robert Armstrong in 1986.

In any assessment of the historic importance of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, the Irish diplomats who had delivered it in November 1985 paid special attention to the opinions of British cabinet secretary Sir Robert Armstrong, who had done so much to persuade prime minister Margaret Thatcher to sign it in the first place.

In September 1986, Armstrong confided to Irish ambassador to London Noel Dorr that the agreement had resulted in “a fundamental change”, adding that “nothing will ever be the same again in Northern Ireland”. Although it was taking a long time for the Unionists “to adjust to that and accept it”, he thought it right that this process “be allowed to work itself through fully”, counselling patience until this happened. But within days , Armstrong was telling Dorr that a cornerstone of Dublin’s policy, the proposal for three-judge courts in Northern Ireland, had been denounced at the special Cabinet sub-committee by Viscount Hailsham, who as lord chancellor, had responsibility for the judiciary.

It was, said Armstrong, “a case of all the guns and the battleship blazing”. Richard Ryan of the London embassy staff had already been given a more detailed account “in strictest confidence” by John Houston, political adviser to foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe. Hailsham had made an “extraordinary, impassioned and emotional” appeal, arguing that the Northern Ireland judiciary, “these brave men”, were “owed something”, Houston reported.

Yet the introduction of three-judge courts would be to “impugn their integrity and to insult them”. Were they to be “given the back of the hand by the Government just to give a sop to Dublin?” Attorney general Sir Michael Havers “unexpectedly” agreed. Although it was felt he “had no good reason to go crusading on this issue”, Houston felt Havers, “who wants Hailsham’s job more than anything on earth, was doing Hailsham’s work for him.” And Whitelaw, who had been “vacillating back and forth on this issue”, also came down against. Northern Ireland secretary Tom King, “to the surprise of everyone”, had submitted a paper supporting three-judge courts. Howe had agreed, as had Hurd, “very strongly”. Thatcher, in Houston’s judgement, was “very affected by the wily Hailsham’s argument”; and this meant taoiseach Garret FitzGerald’s prospects of carrying his argument on this question were “grim”.

‘Friendly tip-off’

Dorr gleaned further detail from Tom King when he met him at the Conservative Party conference some days later. King professed to be giving Dorr “a friendly tip-off about some measure of resentment aroused in certain quarters on the British side, by the remarkable extent [his words] to which we have now penetrated the British decision-making system.”

Dorr reminded Iveagh House of the accepted convention in Britain that the mere existence of Cabinet sub-committees, still less their subject matter or conclusions, should not be publicly referred to.

The question for Dorr was whether King was “giving vent to his own suspicious disgruntlement” or whether he was “echoing to me” the resentment of other committee members.

Dorr’s interpretation was that King was “suspicious of our easy access and slightly resentful of it”. Dorr was inclined to put this down “largely to King’s own character”.

And Dorr reported that Havers was also “a bit taken aback” about how much the Irish knew of the British decision-making process.

But Dorr did not think his embassy staff should be “frightened off” from their endeavours as there was “nothing in the manner of our lobbying” which should cause any resentment.

The 1986 files are replete with reassurances from Thatcher that the Anglo-Irish Agreement would be implemented.

This was as much her insistence that she would not be intimidated by Unionist or Loyalist blackmail as by any indication on her part she thought it was delivering what she had been promised.

But after a year of the agreement, Ted Smyth of the London embassy offered his personal observations of the prospects for the agreement for the short-term future.

He believed Thatcher could not be taken for granted.

“For even with Mrs Thatcher none of the old certainties prevail: the lady who was ‘not for turning’ now shows distinct rudder problems on sacrosanct public expenditure policies because of growing public criticism.”

Smyth added that if the British public saw no major improvement in security “that too will affect her commitment”.

And this was another reason why the Irish government would have to demonstrate “again and again to either a sceptical or indifferent British audience that it is able to deliver handsomely on its side of the bargain”.

In a paper The Political Situation in Northern Ireland – one year on to mark the anniversary of the Hillsborough signing, the Anglo-Irish Section of the DFA stated that the majority of Unionists were still opposed to the agreement and believed it could be destroyed.

That it amounted to joint authority had initially taken hold amongst them and had “not yet been dispelled”. as delivering what she had been promised.

Shock to ordinary Unionists

The agreement had come as a shock to most ordinary Unionists “for whom political beliefs and expectations had frozen in 1920”.

And because they had always seen politics as a zero-sum game, they could not appreciate how, if both sides operated from the basis of equality, they could all move forward together.

When Thatcher and Garret FitzGerald met in London on December 6th for their final meeting of the year, the taoiseach expressed concern as to whether he could deliver the revised extradition legislation shortly to come before the Dáil. “If we do not get this, it would be disastrous.”

FitzGerald told Thatcher that Charles Haughey, if elected taoiseach, would not “disturb the agreement”; nor would he disturb any extradition legislation if it was already on the statute book, “though he himself could not, politically, introduce it”.

If passed, the new legislation would come into force in June, without Haughey being required “to take any positive action”, that is, added FitzGerald, “if he is in my position then”.

They later went on to discuss cross-border security, with FitzGerald at one point claiming that forces, north and south, had “a next to impossible border to watch”. To which Thatcher responded: “Yes, we got it wrong in 1921.”

They concluded by reviewing the agreement. Thatcher was relieved the first anniversary had passed “without more trouble”. But it was now “like an open wound”.

When she had first signed it, she believed the Unionists would take reassurance from its guarantees. But now they would “have to settle down with it”.

Nally’s note of the meeting added the observation that Thatcher concluded the exchanges with “rather a wistful reference to whether she could continue, in all seriousness, to send young men to their death in Northern Ireland”.

Dr John Bowman is a broadcaster and historian. His most recent book is Ireland: the Autobiography, published by Penguin any extradition legislation if it was already on the statute book, “though he himself could not, politically, introduce it”.

Democrats face eight hard steps to retake the White House

Despite catastrophic loss to Donald Trump, the pulverised party can still pick itself up

By Ted Smyth

December 28, 2016

“Many working people voted for the guy who said he would change the rigged system.”

Photograph: Getty Images

As Democrats in the US plan a new campaign to win back the White House and Congress, a few lessons can be learned from the recent election. First, Donald Trump’s win was not a decisive victory for Republicans, given that the billionaire TV star, a one-time Democrat, ran as an outsider, shunned by nearly every official in the Republican party. Hillary Clinton would have triumphed if she had not lost by a tiny margin in the key battleground states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. She actually won the popular poll by 2.8 million votes, a bigger margin than any other presidential election. Ironically, the electoral college, designed by the founding fathers to limit the “mischiefs of faction”, officially elected the candidate who stoked the fears of a once-dominant racial majority. Most important, Clinton lost because she allowed Trump to run to her left with working people, those who are facing a growing crisis of low wages and suffocating debt. A more nimble campaign would have said: “Obama deserves the credit for rescuing us from the Republican recession, but working men and women are still getting stiffed. We’ve got to fix the system, which is rigged against ordinary people.” Instead, the campaign seemed to think it could win by building a targeted coalition of women, Hispanics and blacks. This alienated many whites who still represent 70 per cent of the electorate. Many blacks and Hispanics did not vote, and more than half of white women voted for Trump.

Economy, stupid

It’s still the economy, stupid. Twenty-four years after James Carville coined the term, Clinton and her staff forgot this wisdom. Manufacturing wages and benefits have been in decline since the 1980s; in Michigan, hourly pay has fallen from $28 (€26.8) in 2003 to $20 in 2016. Most low-skilled workers in banks and retail stores across the country earn about $10 per hour. The challenge for Democrats is to restore growth and equality to a system that has left more than two-thirds of Americans with flat and declining incomes for the past decade. Since the 1990s, presidential candidates from both parties have promised various fixes to low wages and unemployment, including worker retraining. While business has benefited enormously from trade agreements and technology, the wealth has not been shared. Training programmes have been underfunded and jobs and wages continue to be cut. According to one study, if trends continue, a quarter of American men aged 25-54 will be out of work by mid-century. When Barack Obama ran for president in 2008 and 2012, he represented enough novelty and hope for change that many white working people voted for him. But by the time Clinton ran in 2016, she represented more of the same (even hesitant to support a $15 minimum wage) and many voted for the guy who said he would change the rigged system.

Political theatrics

Trump is quite prepared to say anything it takes to smooth a deal, whether you are a low-wage white guy or the government of Taiwan. You will be literally advised by the Trump people not to believe everything. As we know from his television hit The Apprentice, Trump does have a gift for popular theatre. His “saving” of 800 jobs in Indiana in return for tax rebates was a political win, all the more so when it was criticised by the free market zealots of the Republican Party. Neither Obama, who has saved/created millions of jobs, nor Clinton, who had excellent economic policies, have that sense of theatre. For example, where were the Boss Springsteen concerts in working class Youngstown, Ohio and, Flint, Michigan? Democratic party volunteers wanted them last August, but that was the month Clinton devoted to fundraising among the very rich. Jeb Bush’s defeat in the Republican primary, despite spending $100 million, had already shown that you needed more than money to beat Trump. Trump and Bernie Sanders connected with voters by criticising the corporate system of global elites, which have created rules that benefit capital at the expense of labour. In absence of collective bargaining and strikes, American companies fulfil their fiduciary duty to maximise returns to shareholders at the expense of workers. Many of these shareholders are short-term corporate raiders, who attack corporations possessing strong balance sheets and intimidate management and directors into being more “shareholder-friendly”. This usually results in companies leveraging their balance sheet and going into debt to pay out millions in special dividends to these shareholders.

Disgruntled workers

In return for this munificence, the raiders move on to the next prospect, leaving the company in debt and management forced to cut labour and other costs. The limited power left to disgruntled workers is to stick it to someone every four years in a presidential election. Against this background, here are eight proposals to help Democrats retake the White House in 2020 and win the 10 Senate seats up for re-election in 2018 (in states won by Trump).

1. Accept the economic system is rigged against working people and campaign for solutions, including rebuilding a modern labour movement. Support living wages and portable benefits, which will stimulate demand. Explore novel proposals, such as allowing corporations to capitalise on their human capital (the present value of future compensation) and claim accelerated amortisation of it, just as they can claim accelerated depreciation on physical capital. This will correct the tax bias in favour of investing in automation rather than in people.

2. Be the champion of all working people. Fight for every vote; do not be misled into thinking you can manipulate segments with algorithms and big data.

3. Nominate younger candidates: Nancy Pelosi (76) has been a great liberal House leader, but Tim Ryan, a bright 43-year-old congressman from a working class district in Ohio, represents the future, with New York’s Joe Crowley, chair of the House Democratic Caucus.

4. Challenge the “shareholder first” model of business and join those, including editors at Fortune-Time, attempting to create a model that challenges the domination of unfettered globalised capitalism and offshore finance.

5. Increase gross domestic product growth and create millions of jobs by rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure through legislation that will repatriate billions in overseas earnings, provided it is invested in infrastructure.

6. Ensure there is a competitive presidential primary process in three years’ time, which elects a telegenic, inspirational candidate who represents real change and hope for American working families. Names being floated include senators Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker and Tim Kaine, as well as John Hickenlooper, governor of Colorado.

7. Rebuild the Democratic National Committee with a full-time leader who uses social media to unite a broad Democratic coalition. Fight back against bigotry and hold Facebook accountable for ensuring its algorithm does not give fake news an advantage over truthful news.

8. Finally, at a time when inequality is growing, embrace the Democratic party’s proud history of progressive achievements from Roosevelt to Johnson, which created decades of strong and inclusive prosperity for all Americans. A majority of Americans want a fairer society with well-paying jobs and affordable healthcare, housing and education. This is the majority that Democrats must lead.Ted Smyth, a former Irish diplomat, is a public affairs consultant in New York City

New Ireland Forum helped begin process

of changing hearts and minds

Shift in nationalist demands allowed forum to become launchpad for lobbying

November 14, 2015,

By

Ted Smyth

Fianna Fáil leader Charles Haughey signs copies of the New Ireland Forum’s report in May 1984.

Haughey initially opposed the subsequent Anglo-Irish Agreement. Photograph: Peter Thursfield

Every major political breakthrough requires significant imagination and courage. The Anglo-Irish Agreement was Margaret Thatcher’s Nixon to China moment – like Nixon’s reverse in recognizing communist China, she yielded on her belief that Northern Ireland was “as British as Finchley”. Those of us who were in Hillsborough Castle that November morning, with the loyalist mob smashing windows outside and Thatcher cheerfully rehearsing media questions inside, fully realized how momentous it was that the Iron Lady was for turning after all.

Yes, she came to regret the agreement in later years but, for now, she was on board and would resist subsequent IRA and loyalist attacks with the same ferocity she had displayed against the miners and in the Falklands.

But it also took imagination and courage to redefine Irish nationalism profoundly, without which Thatcher would not have signed the agreement. That was achieved through the New Ireland Forum in 1983-1984 and, for the first time, committed 90 per cent of nationalists on the island to the realities and core principles that underpinned the agreement in 1985.

Most importantly it committed them to the equality principle expressed in chapter five of the forum report, essentially recognizing the validity of both nationalist and unionist identities and the need for both to be reflected and protected “in equally satisfactory, secure and durable, political, administrative and symbolic” form.

During those months in Dublin Castle when politicians from Fine Gael(including future Taoiseach Enda Kenny), Fianna Fáil, Labour and the SDLP met for 28 private sessions, 13 public sessions and 56 meetings of the steering group of party leaders, I was glad to see a transformative education process was under way for all of Ireland.

That the forum had happened at all was a miracle. In previous decades leaders in the Republic, including Éamon de Valera, had refused to entertain all-Ireland conventions to address the Northern crisis. This time, John Hume and taoiseach Garret FitzGerald were in favour of a conference but some Fine Gael ministers were opposed.

In a clever manoeuvre, Hume convinced them to agree by using the possibility that Fianna Fáil leader Charles Haughey would take credit for the initiative. Significantly, the forum was the first time Fianna Fáil agreed to recognition of equal rights for unionists. Unfortunately, at the press conference at the end of the forum Haughey retreated to the comfortable populist corner by playing up the preference of the forum for a united Ireland.

As press officer of the forum I made sure the British and international media were fully aware of the significance of the equality principles and the openness of nationalists to other proposals, including a federal/ confederal state and, most notably, joint authority. Many of us felt strongly that the united Ireland mantra was a dead end that had enabled British inaction for decades and empowered discrimination against northern nationalists.

Remaining obstacles

FitzGerald demonstrated remarkable political skill in not taking the bait in November 1984 when Thatcher, after a meeting in Chequers, brutally dismissed all the forum options. We were with FitzGerald in the Irish Embassy as the reports came in of her provocative outburst but he refused to express public anger. We exploited Thatcher’s rant to gain support from the US media for the forum proposals.

In September 1985 I became head of press at the London embassy, succeeding the very effective Pat Hennessy and Daithí Ó Ceallaigh, as we sought to persuade powerful Westminster lobby correspondents and MPs to support the imminent agreement. Many were receptive but cautious.

Alan Watkins, veteran political columnist at the Observer, was representative of those who were somewhat mystified by the power of Irish nationalism and wondered why the Irish, like the Welsh, couldn’t enjoy being in the British club. In some ways, we had more difficulty with British Catholics, who, somewhat defensively, thought that Catholics in Northern Ireland should just become British.

Richard Ryan, the Irish embassy political counsellor, and I became fixtures in the Garrick and Boodles, methodically engaging, one by one, with MPs, editors, columnists and influencers generally. I had a special pass to sit in the Commons press gallery, facilitating daily engagement.

Our job was to appeal to the British sense of fair play, now an easier task as we were not asking them to rat on their loyalist cousins in Belfast but to grant equal rights to nationalists. Those in the British media who were more consistently engaged in covering the North issue appreciated the important change , including Jim Naughtie and Julia Langdon of the Guardian and Brenda Maddox of the Economist.

In talking to others we were not helped by the lingering perception of Ireland as an economically depressed, priest-dominated country that had stayed on the sidelines in the second World War. Fortunately, growing respect for FitzGerald and Hume, joint membership of the EU since 1973 and the increasing prominence of Irish people in the academic and business life in Britain were changing perceptions.

Strangely, the opposition British Labour Party played a minimal role in the agreement. Its policy of Irish unity by consent, a recipe for inaction since consent was not likely, was designed to placate the Troops Out and pro-unionist wings in the party. It would take more imaginative members such as Peter Mandelson, who had left television production to become Labour’s head of communications, to play a more significant role in the 1990s.

Role of media

The Irish Times Irish Press Irish IndependentIf the road to the agreement was a difficult one, its implementation phase was even more problematic. The Sunningdale agreement had collapsed in 1974 due to lack of commitment by Harold Wilson and the British army. Buoyed by this success, loyalists were sure they could destroy the agreement’s intergovernmental conference and the Maryfield joint secretariat.

But the agreement held fast, first because it was “non-boycottable” (only the two governments were participating) and second because of the determination by Sir John Hermon and the RUC to maintain order.

By the time Haughey, who had opposed the agreement, became taoiseach again in 1987, the benefits of the new arrangements were so apparent that he wrote to Thatcher on her re-election that year, saying he looked forward to bringing lasting peace and stability to Northern Ireland “in the framework that has already been set.”

As the British turned to other pressing issues, including growing London as a global financial centre, it was tough to keep them focused on a host of reforms needed in Northern Ireland, including the courts, police, prisons, economic development, cross-Border co-operation and Irish-language teaching.

Thatcher was angered that the IRA continued to bomb and that there was no clear security dividend from the agreement. There were rows over extradition of IRA suspects from Ireland to Britain; one Conservative MP attacked me for being a “bad European” on the issue at the home of veteran BBC journalist John Cole.

But steady progress towards lasting peace continued to be made thanks to the commitment, courage and imagination of politicians, officials and civic and community leaders from both islands. Above all, the integrated actions of the Irish and British governments over the years has led to an interdependent relationship and mutual respect that provides the essential framework for equality and stability in Northern Ireland.

Ted Smyth was a member of the secretariat and press secretary of the New Ireland Forum

and head of press for the Irish Government in London from 1985 to 1988.